IMPORTANT: Myasthenia Gravis must be diagnosed through a veterinarian as you need specific testing done and sent for evaluation. After receiving results, your veterinarian will help determine the plan forward for your dog. This condition does have possibility for your dog to go into remission.

Myasthenia Gravis (MG):

The Latin meaning is “grave muscular weakness” and the most common form of MG is a chronic autoimmune neuromuscular disorder that is characterized by fluctuating weakness of the voluntary muscle groups. MG is a painless disease meaning here is not pain associated with the weakness they are experiencing.

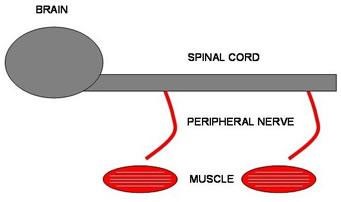

What is the neuromuscular system:

The nervous system is divided into the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and peripheral nervous system (also called neuromuscular system, composed of nerves and muscles). The neuromuscular system consists of the nerves leaving the back of the brain to innervate muscles and glands of the head (cranial nerves), and peripheral nerves leaving the spinal cord to control in particular the muscles of the limbs. The junction between the peripheral nerve and the muscles is called the neuromuscular junction.

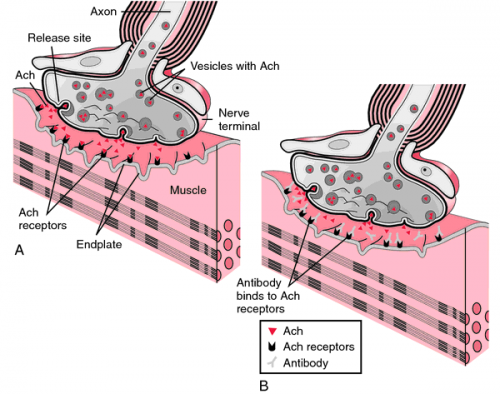

A chemical messenger called acetylcholine (pronounced ah-See-tul-KO-leen) bridges this gap. This messenger is released from the end of the nerve, flows across the gap and fixes itself to a specific receptor (acetylcholine receptor) on the muscle. The acetylcholine attaches to the receptor (like a key fitting a lock) and triggers a signal, which causes the muscle to contract.

In Myasthenia Gravis, there is abnormal transmission of the message between the nerves and the muscles. In the body of an MG dog there is a reduction of the number of receptor sites. The reduction in the number of receptor sites is caused by an antibody that destroys or blocks the receptor site. Antibodies are proteins that play an important role in the immune system. They are normally directed at foreign proteins called antigensthat attack the body. Such foreign proteins include bacteria and viruses. Antibodies help the body to protect itself from these foreign proteins. For reasons not well understood, the immune system of a dog with MG makes antibodies against the receptor sites of the neuromuscular junction. Abnormal antibodies can be measured in the blood of many dogs with MG. The antibodies destroy the receptor sites more rapidly than the body can replace them. Muscle weakness occurs when acetylcholine cannot activate enough receptor sites.

There are two types of Canine Myasthenia Gravis:

Congenital Myasthenia Gravis:

In this condition, the patient is born without normal neuromuscular junctions to striated muscles. There is no effective treatment. Myasthenia Gravis has been described as a recessive genetic disease in Jack Russell Terriers, Springer Spaniels, and Smooth Fox Terriers. The Miniature Dachshund gets a congenital form that actually resolves with age.

Acquired Myasthenia Gravis:

This is a so-called autoimmune disease, meaning the immune system is destroying neuromuscular junctions as if they were foreign invaders. What muscles are affected depend on which junctions have been destroyed. Therapy centers on stopping this immune reaction and prolonging what acetylcholine activity is still present. This is done with a combination of immunosuppressive agents and medication to inhibit acetylcholinesterase. Acquired Myasthenia Gravis can be further divided into three categories:

Group 1: Mild or Focal MG – only one body part, usually the esophagus, is involved.

Group 2: Moderate Generalized MG – appendicular (limb) weakness with or without Megaesophagus.

Group 3: Severe Generalized or Acute Fulminating – rapidly progressive and usually fatal.

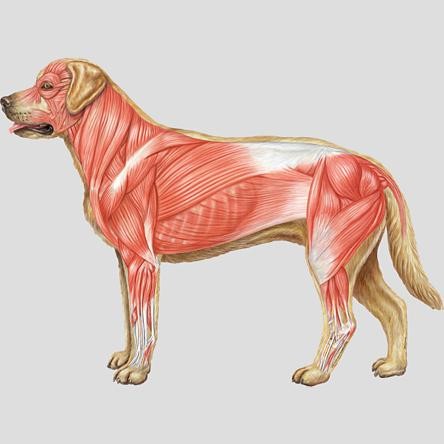

MG affects the striated voluntary skeletal muscles of a dog. Take a look at the illustration above; notice the heavy concentration of muscles in the neck area and hind quarters. This is why 90% of dogs with MG also have Megaesophagus. It is the reason why hind leg weakness is also a tell tale sign of MG.

Signs and Symptoms:

Symptoms can vary from dog to dog. A dog may have one symptom or many.

– Megaesophagus

– Bark Change (usually high pitched)

– Hindquarter weakness or limb weakness – Sudden urge to “sit down”. Weakness appears after exercise and condition improves after rest.

– Blink Reflex (Palpebral reflex) – A reflex elicited by touching the eyelid and observing for a blink. This response fatigues or is absent in animals with MG. (watch how to test for Palpebral Reflex) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4_zdjL51qoU

– Walking with stilted rear legs, quivering or shaking rear legs, running sideways, unable to jump or climb stairs. (ex. of MG rear weakness) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZBR686banRc

– Drooping lower lip – sudden increase in drool due to weakness in lower lip

– Drooping tail

– Trouble controlling urine stream or holding squat while defecating

– Lethargy

Diagnosis:

If Congenital Myasthenia Gravis is suspected, it is recommended that your veterinarian contact Dr. Diane Shelton directly through the website Comparative Neuromuscular Laboratory @ http://vetneuromuscular.ucsd.edu/index.html A muscle biopsy will need to be sent. Congenital MG cannot be detected by blood test.

For Acquired Myasthenia Gravis, a blood test can be done to check for antibodies against acetylcholine receptors. It is called an AChR test. This blood test is able to detect 98% of pets with myasthenia gravis. When antibodies drop to less than 0.6 nmol/L, clinical signs generally resolve. Serum should be collected before corticosteroid therapy is initiated because immunosuppressive doses of corticosteroids for longer than 7-10 days lower antibody concentrations.

Seronegative myasthenia occurs in approximately 2% of dogs. The percentage of positive tests in the focal form of MG may be slightly less, but currently there is no other way to diagnose the form of MG. If the vet strongly suspects MG and antibody test is negative, the positive clinical findings probably should take precedence over negative confirmatory test and a diagnosis of possible MG should be made and treatment should be started. If clinical signs were recent in onset, retesting in 1-2 weeks may confirm the diagnosis. The test is available through one lab, Comparative Neuromuscular Lab at the University of California, San Diego, in LaJolla, CA. The test takes between 5-7 business days to perform after it is received.

Tensilon Test:

This test involves giving an injection of edrophonium chloride (brand name Tensilon) intravenously to a patient suspected of having myasthenia gravis. Edrophonium chloride is a short-acting anticholinesterase. This allows acetylcholine to accumulate in the neuromuscular junction, strengthening the message from nerve to muscle. A dramatic increase in muscle strength following the IV injection should give a presumptive diagnosis of acquired MG while waiting for the results of the AChR antibody titer test. Treatment could be initiated based on the results of the dramatic positive test. Unfortunately, not all dogs are responsive to Tensilon, and dogs with other neuromuscular diseases may show a subjective positive response.

Watch Buddy’s positive Tensilon test: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k7YX9kuWrxA

Watch focal MG pre and post positive Tensilon Test: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-13EIGGP4bk

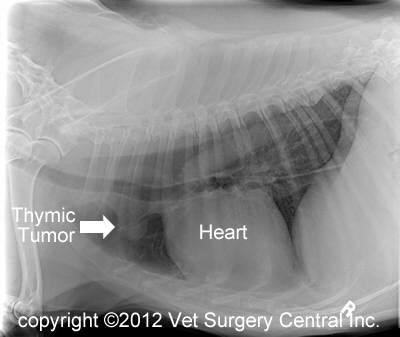

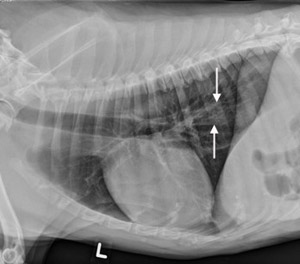

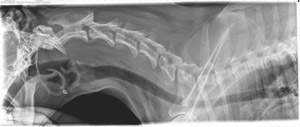

Chest Radiographs (X-Rays):

A chest radiograph set should be taken to check for thymoma. A thymoma is a tumor on the thymus gland. Surgery to remove the tumor is sometimes recommended for patients who have thymic masses so it is important to identify these patients. Thymoma may be associated with an acute, fulminating MG. Thymoma is much more prevalent in cats. In dogs, only around 3-4% of patients will fit this category. See the Thymoma chapter for more detailed information if/as needed.

Thymoma

Another reason to take a chest radiograph is to look for megaesophagus and aspiration pneumonia.

Treatment:

Anticholinesterases are the first line of defense. Pyridostigmine is the typical medication used to prolong the action of acetylcholine. Neostigmine is also sometimes used although Pyridostigmine is preferred for fewer side effects. By inactivating acetylcholinesterase, the receptors that have not been destroyed by the immune system can bind acetylcholine longer. It is typically given orally 2 to 3 times daily with food. The syrup form should be diluted with equal parts water. It comes in syrup, tablet and time span forms. Close supervision with your veterinarian is advised in regards to dosing these drugs. If patient exhibits signs of worsening weakness, vomiting, cramping, diarrhea, tearing or drooling the vet should be notified immediately. Many canine patients will require no further treatment beyond this medication.

Sometimes corticosteroids, immune-suppression drugs (like prednisone, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclosporine) may be used if clinical signs of MG are not completely relieved with anticholinesterase drugs.

Prednisone is a synthetic drug taken by mouth that resembles natural hormones produced by the cortex of adrenal glands. The body depends on these hormones, called corticosteroids, during stress. Prednisone has a great many potential undesirable effects in dogs including suppression of adrenal gland functions, marked muscle weakness, and muscle atrophy. Unique to MG is the possibility of increasing weakness during the first two weeks of prednisone therapy. This necessitates close medical supervision when prednisone is instituted, either on an outpatient or in-hospital basis.

Azathioprine also may be of use in canine MG but side-effects require frequent monitoring of blood counts to detect rapid drops in the number of white and red cells in the blood, and periodic liver function tests to detect potential toxicity to the liver.

Mycophenolate Mofetil MMF (brand name CellCept) is an immuno-suppressant drug used for the treatment of autoimmune conditions such as AIHA, some types of cancer and as an anti-rejection drug for human organ transplant recipients. Mycophenolate Mofetil can take much longer than prednisone to suppress the immune system so treatment response may not be seen immediately.

Cyclosporine is a medication also used to treat tear deficiency problems. However it may also cause eye irritation if topical medication is made from oral cyclosporine. For dogs it can also cause callusing of the footpad, muscle cramps, weakness of muscles, tremors, or restlessness.

Medications can be complicated and must be monitored closely by you and your veterinary care professional.

Remission:

Unlike humans, canines can actually go through spontaneous remission sometimes as early as four months after first clinical signs. The average time for remission is 6-8 months, with some dogs taking over a year to go into remission. Many times the megaesophagus resolves as well.

Prognosis:

Prognosis is good! As long as the symptoms of megaesophagus are well managed to lessen the danger of aspiration pneumonia, your pup has a good chance of kicking this thing!

Follow up and tips:

– Periodic chest x-rays and AChR antibody titer test are suggested to monitor the disease until remission is achieved. Many Neurologist DVMs suggest every 3 months.

– Wean off of meds slowly with your vets guidance. Let your veterinarian be the toxicologist with the cocktail of drugs.

– Avoid stress whenever possible. Excessive heat or cold, and overexertion can exacerbate symptoms.

– Do not vaccinate. Please discuss this with your veterinarian.

– Trust your gut. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact your vet and get in for an exam.

– Stay vigil. Relapses do occur. Sometimes the same muscle groups are affected, and sometimes it can look completely different.

– Stay in close communication with your vet, especially in the early days. Daily check ins are really important, whether it be by phone or email with pictures and/or videos.

– If your vet is not knowledgeable about the disease, and does not want to consult with specialist to help your dog, find another. Look for a Neurologist DVM.

– Keep a daily log on what meds are administered and when. Record any reaction your pup may have; progress or set backs.